Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterised by difficulties in social interaction, communication, and restricted or repetitive patterns of behaviour. Early identification and intervention are keys to improving outcomes for individuals with ASD. Clinical screening plays a crucial role in the early detection of autism, often before a formal diagnosis is made.

Clinical screening serves as a first step in identifying children who may be at risk for ASD. Since ASD can present with a wide range of symptoms and severity, timely screening allows for:

- Early intervention: The earlier a child receives support, the better the potential developmental outcomes.

- Improved prognosis: Children who begin therapy early tend to make more significant gains in language, social skills, and cognitive development.

- Guidance for families: Screening provides families with resources and direction, reducing uncertainty and stress.

Clinical Screening

Developmental surveillance is incorporated into the Sri Lanka healthcare systems at the primary care level.

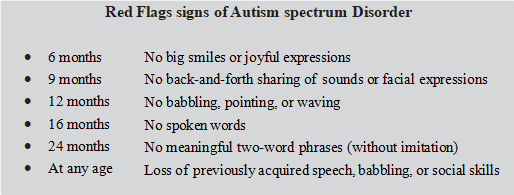

Early signs of autism usually appear in the following key developmental areas:

- Social Communication and Interaction

- Limited eye contact (may not look at people’s faces during interactions).

- Does not respond to name by 9–12 months.

- Lack of shared/joint attention – does not point to show interest or follow someone else’s pointing.

- Few or no gestures such as waving, clapping, reaching.

- Does not show interest in others – less likely to smile socially or seek comfort and does not like hugging.

- Poor imitation skills – does not copy facial expressions, sounds, or actions.

- Speech and Language Development

- Delayed babbling (no babbling by 9 months).

- Lack of meaningful words by 16 months.

- No two-word phrases by 24 months (not including imitations) and three-word phrases by 3 years.

- Unusual tone or rhythm of speech (monotone, sing-song, or robotic voice).

- Limited use of language for social interaction (more likely to repeat words than use them to communicate).

- Speaking in an abnormal tone of voice or with an odd rhythm or pitch.

- Repeating words or phrases over and over without communicative intent – echolalia.

- Trouble starting a conversation or keeping it going.

- Difficulty communicating needs or desires.

- Doesn’t understand simple statements or questions.

- Repetitive Behaviours and Restricted Interests

- Repetitive movements (e.g., hand-flapping, rocking, spinning) moving constantly.

- Fixation on specific objects or parts of toys/Obsessive attachment to unusual objects (rubber bands, keys, spinning wheels, flipping switches).

- Rigid routines and distress with change, A strong need for sameness, order, and routines (e.g., lines up toys, follows a rigid schedule). Gets upset by changes in their routine or environment.

- Unusual sensory interests or responses (e.g., smelling toys, aversion to certain textures or sounds).

- Preoccupation with a specific topic of interest, often involving numbers or symbols (maps, license plates, sports statistics).

- Clumsiness, abnormal posture, or odd ways of moving.

- Fascinated by spinning objects, moving pieces, or parts of toys (e.g., spinning the wheels on a race car, instead of playing with the whole car).

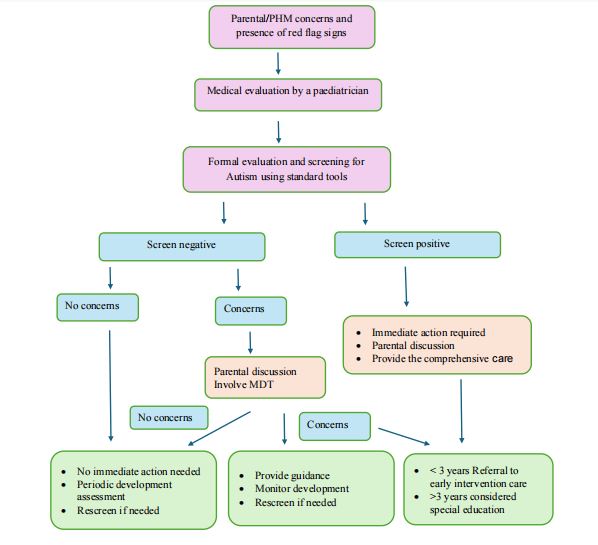

What to do if you notice these signs?

- Talk to your child’s doctor: Don’t wait—early screening tools like the M-CHAT-R can help assess risk.

- Request a developmental evaluation: Paediatricians will refer to a developmental paediatrician, child psychologist, or early intervention service.

- Don’t wait for a diagnosis to act: Early intervention programmes can begin even before a formal diagnosis is made.

Challenges in Clinical Screening

Despite the availability of tools and guidelines, several challenges are seen:

- Limited Access to Trained Professionals – There is a shortage of developmental paediatricians, child psychologists, speech therapists, and occupational therapists, particularly in rural areas.

- Urban-Rural Disparity: Most diagnostic and early intervention services are concentrated in major cities, leaving many families in remote regions underserved.

- Social stigma: especially in these parts of the world, the stigma hinders screening and seeking early intervention.

- Variability in presentation: Autism symptoms can differ widely across individuals, making standardised screening more difficult.

- Cultural and socioeconomic barriers: Access to healthcare and screening may be limited in some populations, leading to disparities in diagnosis.

- False positives/negatives: Screening tools are not diagnostic and may sometimes fail to identify children with or without ASD accurately.

- Parental awareness and participation: Screening often relies on carer input, which their knowledge and perceptions of development can influence.

Clinical screening for autism is a vital part of paediatric healthcare, enabling early identification and intervention. While screening is not a substitute for comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, it plays a foundational role in recognising children at risk. Continued efforts to improve accessibility, accuracy, and public awareness are essential for optimising outcomes for individuals with autism and their families.

![]()

![]()

![]() Paediatric development screening flowchart

Paediatric development screening flowchart